Many people own land. It can be a place to live, or an investment, or both. Land can also be owned by more than one person.

There are two general ways in which land can be co-owned; as joint tenants or tenants in common.

- Joint tenants each own 100% of the land together in undivided shares. For instance, a husband and wife often own their family home as joint tenants, which is to say, they together own the entire property.

- In contrast, tenants in common own 100% of the land, but in divided shares. For example, three people may own a commercial property in equal shares of 1/3 each. Each owner’s 1/3 share is listed on title to the property.

Sometimes co-owners of land get into disagreements about how a property should be administered or whether to retain or sell the land. It is not uncommon that one co-owner of a property wishes to sell it and the other co-owner does not.

How are such disputes resolved?

Prudent landowners may choose to enter into a contract prior to purchasing land with another person which provides a mechanism for dealing with disputes. However, in many instances, land is simply purchased without regard for a way to deal with potential future disputes.

In Ontario, the Partition Act provides some assistance to co-owners of land who are in a disagreement. Under the Partition Act, an owner of land may apply to the court to force a sale of the land. However, this right is not absolute. The person seeking the sale of the land must have what is known as a “possessory right” to the land. To take an example, if a co-owned commercial property is leased to a tenant, one co-owner cannot force a sale of the land since there is a tenant with a lease who is occupying the property. Moreover, assuming that a co-owner has a prima facie right to sell a property, a court may still refuse to order a sale if the moving party’s intent is malicious, oppressive, or vexatious towards the other co-owner.

Case Study

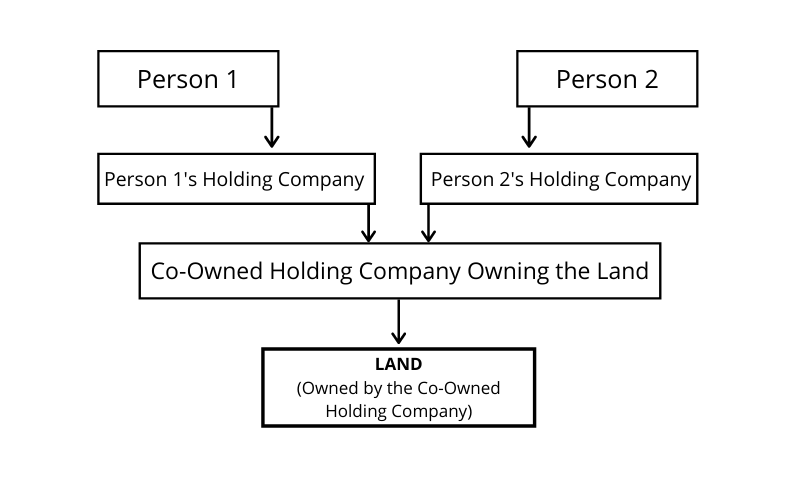

A recent interesting case involving the Partition Act is Galsan Holdings Inc. v Davalnat Holdings Inc.[efn_note]2018 ONSC 3600.[/efn_note] In this case, two individuals owned land through a series of holding companies, which can be illustrated as follows:

In this case, Person 1, who, through his holding company, which owned shares of the Co-Owned Holding Company, sought an order that the land be sold. The court dismissed the application of Person 1 and Person 1’s Holding Company.

The land in this case was owned by the Co-Owned Holding Company, not Person 1 or Person 1`s Holding Company. Person 1 (nor his holding company) had an interest in the land, let alone a possessory interest. The land was owned by another co-owned company.

This case illustrates the importance of foresight in how land is owned. There can be advantages to owning land through corporations. However, corporate structures of ownership can have the effect of depriving a person of the relatively simple and easy process of forcing the sale of land under the Partition Act, and force more complicated and costly proceedings when parties are in a dispute.

These comments are of a general nature and not intended to provide legal advice as individual situations will differ and should be discussed with a lawyer.